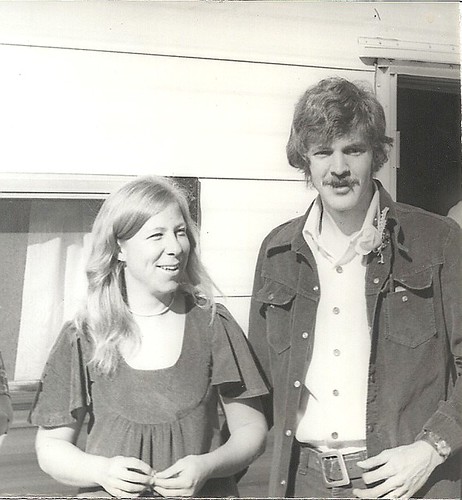

All we had for a map, when our little convoy entered Los Angeles County, was one of those general state maps, the kind the gas stations used to sell, with the major highways shown but with very little detail about the major cities. Thus, when we drove into the city of Los Angeles, we exited the freeway at some distance west of our final destination. I found the street we were seeking, but we had some way to go to reach the address where Carol’s sister was renting a house. We were going to rent space in that house for a while until we figured out what we were going to do in Los Angles. As we drove through the city, which I was later to learn was Hollywood, the neighborhoods appeared to be somewhat less than desirable. Certainly, I thought, this is not anywhere I want to live. As we got closer to the address of the house, the neighborhoods got better and better and I was encouraged. When we found the house, it turned out to be a rather nice old place in what appeared to be a clean and safe neighborhood.

If, in the course of this tale, I’ve given you the impression that we simply sold almost everything we owned in Colorado, packed up the rest and moved to Los Angeles without any other plan, you’d be correct. What the hell, we said. We didn’t have a plan when we were living in Steamboat Springs, why would we need a plan in Los Angeles? Really, I mean it’s Los Angeles, the Big City, Land of Opportunity, Home of Hollywood. What could go wrong? Okay, sure, it’s 104 degrees, our cars barely survived the trip and we’re moving into a house already full of people, some of which are teenagers, but, hey, it’s California, right? Yep, look out Los Angeles, we have arrived!!

A brief word of advice for anyone who is planning on selling almost everything, packing the rest in a truck and heading off to some other city: Always Have a Plan. Always. Have a Plan. Always. Fly out to the place you are thinking of moving to and do a bit of exploring. While you are there, line up some possible jobs, get an idea of the cost of living, do a bit of research on the economy and the culture. When you have done all that, go home and put together a plan. Make a few phone calls to the contacts you made in what will be your new home. Set up a few job interviews. Get hired to work for someone at a salary that will make it possible for you to afford to live in your new home. Put down a deposit on a place to rent. Then, when you arrive, you can move into your new digs, report for your new job and be confident in your future. Or you can do it the way we did it, with no plan, no research, no jobs and no clue.

After we unloaded the truck and unhooked the cars from each other, we sat on the front porch of the house where we were going to be living and had a glass of half-strength lemonade, made from concentrate. It was still brutally hot and we were exhausted. Carol’s sister Terry took us out for a walk, down three or four blocks to the House of Pies. The House of Pies was great, it had an all-American menu and they served pies and ice cream, lots of different pies and lots of ice cream. From then on, it was a tradition. Anyone who came to visit us was, at some point, treated to a walk and some sugary dessert at the House of Pies. We had another landmark, another point from which to navigate the great unknown City of Los Angeles.

One of the first things that I discovered after we had settled into our new home was that neither of our cars was working. Actually, I had heard, as we drove in, an extremely loud squeaking sound from the underside of our big Jeep Wagoneer. Once we got it parked I discovered that the constant velocity joint on the driveshaft was completely worn out; so worn, in fact, that it was almost a miracle that we had made it as far as we had. When I went to start up the little VW station wagon, it too was making a very loud sound. The bolt holding the engine cooling fan had rattled loose on the trip out. Once I got it tightened up, the car seemed to run just fine, so we, at least, had a way to get around the city. We were going to need that car, and the Jeep, too. As everyone else already knew, and we were immediately to discover, Californians love their cars. That’s not to say that there are not lots and lots of buses travelling all around the streets in Los Angeles; it’s just that, most of the time, the bus doesn’t really go where you need to be at the time when you need to be there. If you are willing to arrange your schedule around the length of time it will take you to get to any given place by bus, it is quite possible to get around that way, but a good part of your day will be spent on buses. That’s fine and it works, if you have no other way to get around, but the most popular and convenient method to get around the city is by private automobile.

I understand that in some cities, it is possible to get around quite easily using the public transportation system; places like Chicago and New York, for instance. Los Angeles is not like those places. Chicago and New York have neighborhoods where everyone lives in apartment buildings, with apartments that are stacked up top of each other and side-by-side for blocks and blocks. Los Angeles is made up of little suburbs filled with single-family homes, interspersed with an apartment building or some condominiums here and there. Everything is spread out for miles and miles and miles. There is just no way that any sort of existing public transportation technology can deal with the way Los Angeles is laid out. Perhaps if we ever get those anti-gravity belts we’ve been promised, there will be a more efficient way to get around in Los Angeles, but, until we do, you need a car.

The next thing I discovered was that all of the things that Carol and I had been doing in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, which had been in great demand and had produced a nice, viable income for us, were already being supplied in great abundance by many other people. We were now very, very small fish in a very, very large ocean. I say “ocean” because there are no sharks, killer whales, giant squids, or krakens in a pond, not even in a big pond. Here in Los Angeles, there be monsters and they will gobble you up if you don’t keep your wits about you. We were strangers in this big city and we were going to have to figure out how to make a living in it. There was no going back. We had to learn to navigate these dangerous waters and quickly. Carol began looking for secretarial jobs and, having actual skills in that area, was soon gainfully employed in the practice of her craft.

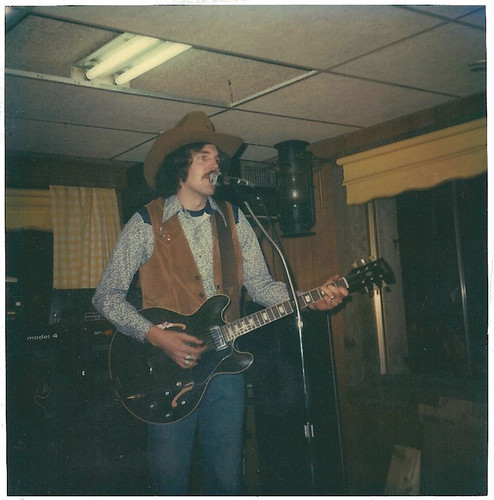

My marketable skills were then, as they are now, difficult to describe and, thus, not really very marketable. I did manage to get some work providing data-base entry and transcription services for a public relations company, and I helped write a few articles and a program manual for a dentist. What I really wanted to do was get back into the music business. I played some open-mic nights and went to some country-western bars. I played bass in a couple of showcase bands. I got one gig playing for a hay ride for one night. That was fun, but it wasn’t quite what I had in mind. I scoured the newspaper want-ads looking for someone who might need what I could do, but there just wasn’t much call for my style of music in the Los Angeles market. I don’t recall exactly how it came to be, but eventually I found this open-mic night in Burbank that featured country music. I started hanging around there, playing a couple of songs every week, and getting to know the other people who showed up to play. I discovered that the country-western community in Los Angeles was much the same as the one that I had left in Colorado; there were the “cool” people, the ones who were already part of the “in” crowd, and there were the people like me, the newcomers, the unproven. I was back at bottom of the ladder, but at least I had found the ladder. This time up the ladder I was bringing some experience with me and that made a big difference in how quickly I was able to get back into the business.